RESOURCES

By Lin Qi | China Daily |

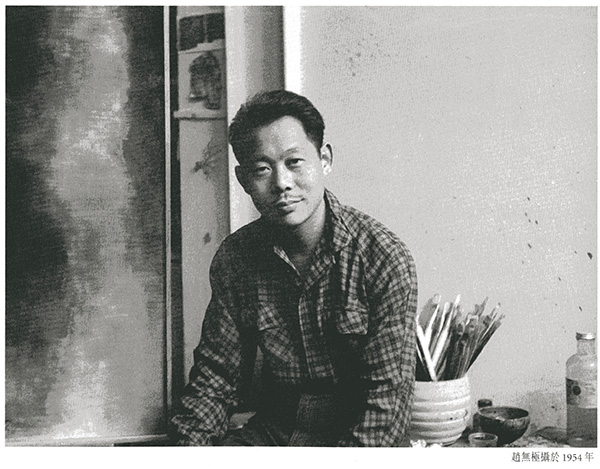

A photo of Zao Wou-ki taken in Paris in 1954.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Modern artists Zao Wou-ki (1920-2013), Chu Teh-chun (1920-2014) and Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010) are often referred to as the "three musketeers" for standing at the crossroads of Chinese and Western cultures and synthesizing the spirits of both in their paintings.

They attended the China Academy of Art in the 1930s and were members of the 200-year-old Academy of Fine Arts of France.

The three masters approached oil painting from the perspective of traditional Chinese culture but were inspired by different things and developed distinctive styles.

Chu embraced the elegant temperament of Song Dynasty (960-1279) landscape painters. Wu felt resonance with the works of 17th-century artists. Zao displayed a preference for the studies of bronzewares from the Shang (c.16th century-11th century BC) and Zhou (c.11th century-256 BC) dynasties, the 3,000-year-old oracle bone script and kuangcao, the wild cursive style of Chinese calligraphy.

Zao translated these ancient forms of Chinese civilization into a modern context, incorporating their elements into his explorations of abstract art.

His paintings won him international prominence in the post-World War II era when abstract art reached its zenith.

Several of Zao's works showing his successful fusion of Eastern and Western cultures will be auctioned in a Sotheby's sale in Hong Kong on March 31.

Untitled, a painting dated to 1958, is from a so-called "oraclebone period" that Zao actively plunged himself into in the 1950s.

Zao Wou-ki's oil painting, Untitled, will be auctioned in a Sotheby's sale in Hong Kong on March 31.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Its brownish and green colors show the inspiration Zao sourced from the archaic bronzewares, while he adopted the mysterious inscriptions on the ancient oracle bones, transforming them into powerful strokes.

Felix Kwok from Sotheby's modern Asian art department says the 3,000-year-old oracle bone script, recognized as the earliest-known writing system in East Asia, was undiscovered until the late 19th century. Zao's father, a banker in Beijing, was one of the first collectors of inscribed oracle bones.

He says this allowed Zao to nurture an early interest in oracle bones that later developed into a scholarly penchant.

Zao moved to Paris in the late 1940s and spent most of the rest of his life there. And seeing a lot of abstract art, Zao, a trained oil painter, turned to the old symbols to find his own style.

Speaking about Zao's work, Kwok says: "Among Chinese artists at the time who studied and borrowed elements from oracle bones, Zao was a representative figure whose painting method demonstrates his thorough understanding of the form."

"And his style won him global recognition."

Untitled was bought by Samuel Rosenmann, the US lawyer and first official counsel to the White House, who donated the painting to the prestigious Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1964.

Zao embarked upon travels around the world in the late 1950s, and experienced an even more vibrant wave of art in the United States.

He began evolving from the oracle-bone period to the hurricane period, during which he demonstrated an even bolder and more experimental approach to abstract paintings.

Also, he explored his ideas on large formats that were well received in the US market.

Zao once said: "Painting is a struggle between the canvas and me, a physical struggle. It is especially true when dealing with works on large formats. One must be fully committed to them."

Another two paintings, titled 19.01.61 and 15.02.65, to be sold in Hong Kong also came from this period.

In the works, Zao presents a dynamic composition, often with a central axis running across the canvas. And there you can see that he fostered an eye-arresting palette and energetic brush strokes, reminding one of the wild cursive kuangcao style of Chinese calligraphy.

In his works he also achieved a manner of grandeur and sophistication that can be traced to the spirit of classic Chinese mountain-and-water paintings.

The explosive feel of Zao's works of the period gives a full expression of his confidence in art and life.

"I don't fear aging. Nor do I fear death," Zao once said.

"I'm fearless as long as I can hold paintbrushes and layer paint."