RESOURCES

By Zhao Xu | China Daily | Updated: 2022-10-15 16:19 |

About 100 pieces of Chinese enamelware are on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Illuminating Chinese art history with their splendid hues, these wares bear witness to cultural exchanges going back centuries, Zhao Xu reports in New York.

What would be the most apt words to describe the domestic ambience of a literary-minded man living in 14th-century China, during the Ming empire (1368-1644)? To a modernday person who has dabbled in the country's aesthetic history, likely candidates would be "sober" and "demure", bearing in mind the succinct lines and dark colors of the now-hailed Ming-style furniture.

Well, all the writing tables, armchairs and wardrobe cabinets on display in one of the Chinese galleries on the second floor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York prove they would be right.

But only partially, says Lu Pengliang, assistant curator of the museum's Asian art department. In a sequestered space on the third floor, Lu has quietly amassed a clamorous show, with nearly 100 pieces of Chinese enamelware, almost all dating to the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. With bold colors bordering on boisterous and patterns intricate to the point of intoxicating, the exhibits, from fruit plates and flower vases to incense burners and snuff bottles, beckon viewers with a flight of fancy into history.

"The sheer number of Ming and Qing enameled wares that have been found and the multitude of purposes they served testifies to their role: people lived with and amid them," says Lu, who titled the display Embracing Color: Enamel in Chinese Decorative Arts, 1300-1900.

The exhibition opens with a prelude, in the form of a bluish-white porcelain vase from around the 13th century. With its swirling carved pattern silenced by a glacial sheen, the vase exudes a calmness and a composure that China's elite literati valued.

"Polychrome porcelain enjoyed an elevated status in Chinese art history for a long time," Lu says, pointing to a collector's manual from the late 14th century, which described cloisonne enamels as "out of place in a scholar's study" for its perceived visual excess.

Yet 68 years later, in a revised version of the book, the new author reversed his predecessor's judgment, calling cloisonne enamels of the imperial court "delicate, sparkling and lovely". What happened in between the two editions was the royal family acquiring taste for color, which in turn led to the new aesthetic's adoption throughout society, Lu says.

"In a sense, it was more about who set the standard for beauty than about beauty itself. This is not to discredit the technical tour de force that had allowed this to happen."

About 100 pieces of Chinese enamelware are on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Cloisonne enameling, used in the West since ancient times, entails affixing thin metal strips to the pre-drawn surface of a metal object. This creates many small compartments — the French cloisons means partitions — into which a paste of finely ground, colored glass and water is placed. The piece is then fired, turning the glass into enamel and fusing it with the metal. Often the enamel shrinks, and a second or even a third application and firing is needed to fill the cloisons completely.

Contemporary writings of the Ming era traced cloisonne enameling, believed to have been introduced to China in the late 13th century, to the Arab empire (632-1258) and the Byzantine empire (395-1453), in the latter case the art peaking in the 12th century. While the Byzantine cloisonne often used gold featuring miniature-sized religious objects, Ming cloisonne had colors bursting on the copper surfaces of daily wares, with the standing edges of the copper strips polished and gilded to contrast with the objects' signature turquoise and lapis blues.

The blues, which gave rise to the Chinese name for cloisonne enameling, jingtailan(jingtai is the reign mark for the seventh emperor of Ming, and lan means blue), were made possible through imported and later domestically produced cobalt pigment, one of the few that can withstand extremely high firing temperatures. In fact, it was the same pigment that led to the production of chinaware painted in underglaze blue, a famed category of Chinese porcelain whose blue-white combination bears a clear Islamic influence.

Not unlike cloisonne, such wares, known as qinghua (blue flower pattern), were initially considered vulgar, before being celebrated and made in large quantities at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty in the mid-14th century. When cloisonne enameling had its own moment soon after, its saturating colors overflowed onto porcelain.

"This was no accident since porcelain had always been what China was known for in ancient times," says Lu, whose Chinese color story is partly centered on cloisonne and partly on porcelain. "Both involved enameling. While cloisonne was never realized on the surface of porcelain, it did every bit to inform its chromatic overglaze."

In the same way copper strips were used with cloisonne, the underglaze blue was employed to draw the outline and provide partition for the varied colors of the overglaze, added during a second firing.

Within those well-delineated spaces, Lu sees an amalgam of influences, ones that had come from far and wide.

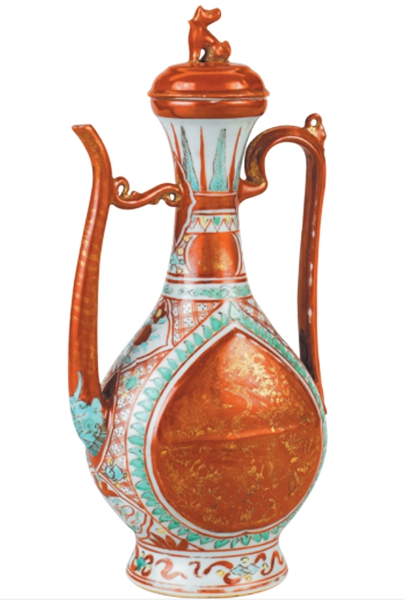

An 18th-century painted-enamel-on-copper-alloy kettle and stand.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Found on several exhibits in the current display is a lotus scroll pattern composed of repeating lotus flowers set within meandering, intertwining tendrils. Now considered archetypal Chinese, it is mostly likely to have traveled the Silk Road from the West, where it had been modeled after acanthus, a plant commonly used to make foliage decoration.

Also traveling the ancient route were Sasanian silverware and pilgrim flasks. The former found their way into a 16th-century porcelain ewer whose red enamel had taken a cue from Chinese lacquerware. The latter, having quenched the thirst of Sogdian merchants and others who had trekked the long road, were reinvented as a pair of luxurious 18th-century cloisonne bottles, both sides densely populated with dragons and tigers, horses and monkeys, alluding unabashedly to the secular pursuit of fame and fortune.

Elsewhere, cloisonne assisted in the spiritual quest, as in the form of a 15th-century base that once supported a three-dimensional ceremonial mandala that probably comprised models of temples and colored sands. If visual intensity could help focus attention and induce piety, a belief central to certain mandala designs, then cloisonne is well-suited to the job.

For Lu, the mandala base testified to the fervor of the Ming court for Tibetan Buddhism. Similar objects have been found in stupas in Tibet and are believed to be the Ming rulers' parting gifts for visiting Tibetan monks, he says.

On a Ming Dynasty cloisonne bowl the Eight Treasures of Tibetan Buddhism — a lidded jar and conch shell being two of them — jostle for space with a miscellany of emblems derived from Taoism and other indigenous beliefs. These include ingots, rhinoceros horns and the Three Peaks, cloud-wreathed worshiping sites for Taoist practitioners.

To further complicate the scene, the center of the bowl's interior base is taken up by the stylized symbol of taiji (yin-yang), a primary force of the universe in Chinese philosophy. If anything, the bowl is the result of a continual effort to adopt, acquire and assimilate, to incorporate something foreign into China's ever-expanding visual art vocabulary.

About 100 pieces of Chinese enamelware are on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[Photo provided to China Daily]

The most salient examples of this effort lie with a small collection of cloisonne and porcelain enamel vases Lu has put on view. Taking the elegant shapes of the ancient ritual bronzes from the Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC), these late reincarnations traded their predecessors' time-honored patina for a vibrant palette exuding a more worldly charm. The ornate patterns, on the other hand, somehow evoke the eye-bewildering and precise surface designs the original vessels had borne.

Around the time several of these vases were made, in the late 17th to 18th century, what Lu calls "the second transformation" was taking place, with the introduction to China of new European enameling materials and techniques.

The new approach, fittingly called painted enamel, offered a much wider range of colors and shades while allowing one to blend seamlessly into another in a way that made possible the vivid depiction of ripening peaches on an 18th-century porcelain plate. The tip of the peach is drenched in a deep rouge, which then gradually dissipates and melts into a pool of light, translucent green as it progresses toward the stem end of the fruit, an effect unimaginable with the previous materials that produced solid, non-mixable colors.

Apart from porcelain, copper-alloy wares also provided canvases for such painterly expressions. The exhibition's accompanying catalogue describes two flower-patterned painted-enamel-on-copper-alloy dishes as having an appeal to "Western traders interested in natural history".

"While royal endorsement had once again proved crucial for the flourishing of this new trend, when it comes to export, the market rules," says Lu, who has deftly woven into the second episode of his color story a narrative strand whose far end extends well beyond the border of China's last feudal empire.

Several painted-enamel-on-copper-alloy exhibits, all from the late 18th and early 19th century, stand out to shed light on this market. One is a moth-shaped inkstand with many compartments that are believed to have held, among other things, ink for a quill pen and wax with which the letter writer could stamp-seal his message. Another is a kettle and its matching stand. Adopting a typical European silverware design, the kettle features blossoms and leaves that echo English country-style tea sets.

"The European market's infatuation with China had already been evidenced by the popularity of Chinoiserie," Lu says, referring to the interpretation and imitation of Chinese style by European artists and artisans through the late 17th century and 18th century, in everything from home deco to garden design. "These Chinese exports, meant to satisfy the same desire, were feeding into and being fed by that phenomenon."

A porcelain ewer in overglaze enamel.[Photo provided to China Daily]

That said, the same creations were aimed at China's domestic market as well, a brightly colored 18th-century porcelain vase that once lit up a Chinese home being graced on its side by two Western women holding a parasol. Its maker used opaque enamels to create shading, giving the images a three-dimensional effect that could also be found in Chinese paintings at the time, thanks in part to the Western missionary-artists who worked in the Qing court.

"The fascination is mutual," Lu says. "But China in the late 18th century was not China in the 14th century."

After banning their ships from the sea and barring foreign ones from coming for more than 400 years, a policy imposed by Ming emperors and reinforced during the Qing Dynasty, China's door was pounded open by British cannonballs during the First Opium War (1840-42). The defeat forced China to open five of its important ports to foreign trade.

These included Canton (Guangzhou in Guangdong), long the sole point of contact between China and Europe. The city, a center of enamel production and distribution for what is known in the West as Canton enamel, retained its position throughout the 19th century. But other enamel works were to leave the country.

In an exhibition of ancient Chinese cloisonne wares at Bard Graduate Center in New York in 2011, two of the exhibits were an art nouveau jardiniere — a decorative flower box or planter — made around 1870 by the Frenchman James Tissot, and another the artist's inspiration: a similar-looking Ming creation he acquired after it was taken when invading Anglo-French troops sacked the Old Summer Palace in Beijing 10 years earlier.

The current exhibition has two painted-enamel-on-copper-plate dishes intended for the Japanese market. Script on the bottom of the dishes reads: "made in the period of Man'en" — Man'en being a reign of the Japanese emperor Komei (1831-67) during whose rule Japan's first major contact with the United States was made, followed by the country's forced reopening to the West. Komei was succeeded by Emperor Meiji, who oversaw a series of rapid social changes that enabled Japan's transformation from an isolated feudal state to an industrialized power.

For some, the dishes serve as poignant reminders of a China whose luster, that once dazzled and captivated just as the painted enamel did, was about to fade.

Since then China has been transformed, while Chinese cloisonne has been reduced to the category of "crafts", indicating an activity inferior to art-making. What was once hailed for its sophistication is now often viewed as ostentatious and garish, if not banal.

"Tastes change," Lu says. "It's not conducive to our understanding of art history to look at a certain moment merely through the contemporary lens. To do that would be to miss the thrill people at the time must have felt, and the pride they took, at being able to create something that could rival the accomplishments of their ancestors, and hopefully make them proud."