RESOURCES

2018-10-31 Source:chinaculture

|

|

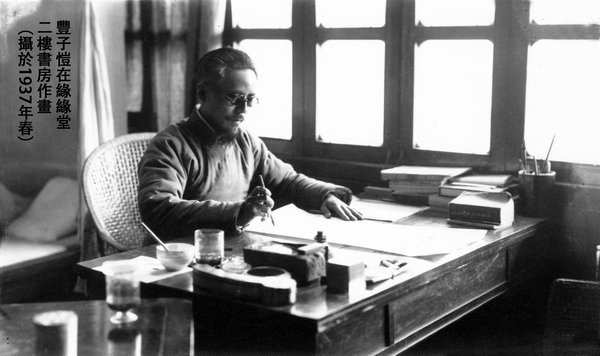

Feng Zikai in his study in 1937.[Photo provided to China Daily]

|

Feng Zikai, the late writer, painter, music educator and translator, is among modern China's most celebrated cultural figures.

Feng (1898-1975) wrote his essays largely drawing from his daily experiences and has provided insights in an approachable, delightful manner. His ink paintings laud the beauty of life in a poetic way while offering witty observations on the complexity of human nature.

The intelligence, generosity and gentle sarcasm that characterizes Feng's oeuvre have created a recognizable style that appeals to many generations of Chinese, healing their hearts, whether during chaotic times or in a fast-paced metropolis.

Feng's extensive fan following, regardless of age or education, is contributing to the popularity of a series of commemorative exhibitions on the 120th anniversary of his birth this year.

Two shows ended on Oct 3 in Hong Kong, one of which witnessed a waiting line at the venue, the Asia Society Hong Kong Center, according to Wang Yizhu, the exhibition curator and a friend of the Feng family that lent the bulk of the exhibited works.

|

|

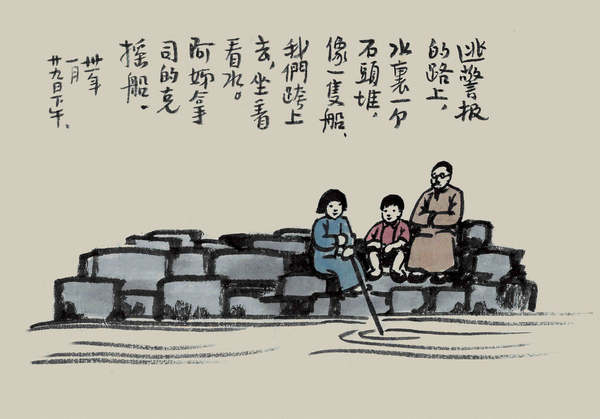

An art piece from the Paintings for Engou album on show in Beijing.[Photo provided to China Daily]

|

A Fair Land This Is, a third retrospective, currently underway at the Zhejiang Art Museum in Hangzhou, and which runs through Nov 11, focuses on the emotional connection between Feng and his second hometown in eastern China where the exhibition is being held. Feng attended a normal school in Hangzhou, not far from his native town of Tongxiang. Hangzhou's landscape and leisurely pace of life helped shape the lighthearted tone in his paintings.

Another ongoing exhibition, Human Comedies, at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing through Nov 4, presents an uncommon juxtaposition of three painting albums-Big Tree, Saving Lives and Paintings for Engou-each from a different collector, but which contribute significantly to a thorough understanding of Feng's views of the world.

The series' last show, Tongxiang My Love, will open to the public on Nov 9.

In 2012, an exhibition of his works occupied four floors of the Hong Kong Museum of Art.

|

|

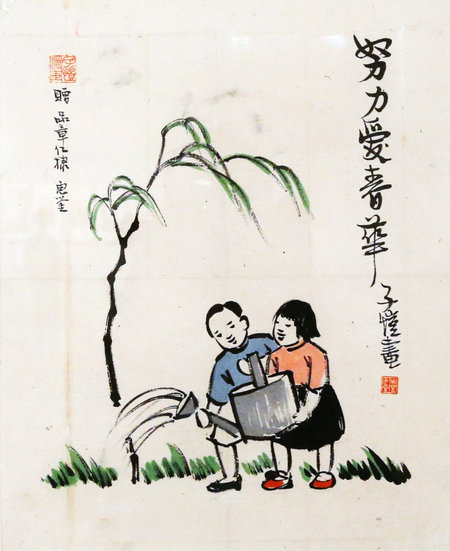

Valuable Spring (Youth), a painting on show from NAMOC's collection.[Photo by Jiang Dong/China Daily]

|

Wang, the curator of the current series, says she was "moved to tears" when visiting the exhibition back then.

She says that Feng is hailed as a man of eminence in cultural circles, but being modest about his talent he may not have wanted to be seen as an icon "worshipped at the sacred temple of art".

Feng's paintings are exuberant with poetic delicacy. He abandoned the sophisticated brushwork of classic Chinese paintings, but retained the liubai (leaving blank areas) approach. He adopted from Western oil paintings the styles of simple, straightforward composition and sketchy, clean-cut strokes.

His works either depict the tranquil, delightful moments of life, no matter how insignificant they look, or gently critique social issues, such as spoiling children and the income gap. His contribution to China's inkbrush art ushered in a modern genre, making it reality-oriented and, as such, more relevant to people.

Feng developed this distinctive language of painting, however, when he thought he had hit a dead end with oil painting.

He went to Japan in 1921 to study oil painting, but soon realized it was impossible for him to achieve perfection in skill and he couldn't afford the expensive art form. Then, he found a collection of works by the self-taught Japanese artist, Yumeji Takehisa, at a street stall. He was inspired by Takehisa's approach, which was less demanding on technique while emphasizing poetry and underlying social concerns.

Some of Feng's critics accused him of "copying" Takehisa, says Wang.

"So, we put together some of their works with similar composition at one of the two shows in Hong Kong," she adds.

Wang says one could see how Feng was inspired by Takehisa, but also formed his own style, grounded in Chinese cultural elements accumulated since childhood.

Feng's paintings emit the beauty of Tang Dynasty (618-907) poetry.

|

|

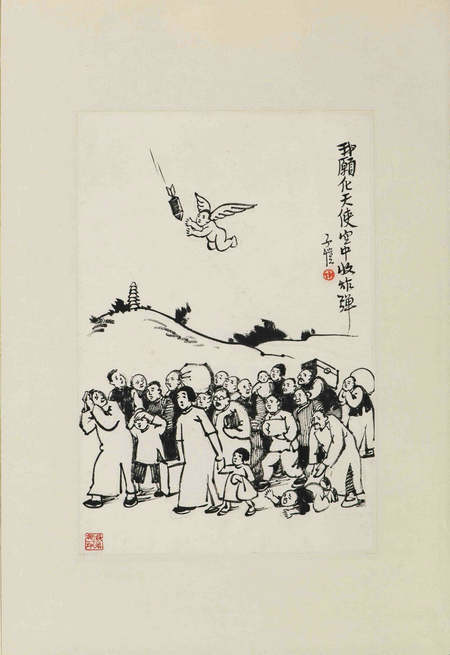

[Photo provided to China Daily] |

He hoped the tree's unyielding spirit would lift up the morale of his people with a firm belief in the final triumph over the invaders.

In a postscript attached to the collection in 2013, Feng Yiyin, his daughter, wrote: "I have vivid recollections of the hardships during our escape. Father would draw or write what he saw then, when he had the time. ... Flipping through this album, I'm overwhelmed with his care for life, his obsession with art and his love for the country."

The same feelings engulf two other painting collections displayed at the Beijing exhibition.

The production of the Saving Lives album, now in the assemblage of the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou, spans from 1927 to 1973. Created out of Buddhist benevolence, the album expresses a merciful attitude toward all living beings.

Feng's work also reflects his admiration of children. He appreciated their innocence, honesty and other qualities that one would find lacking in the adult world. He had seven children, and he drew the Paintings for Engou album in the early 1940s, which records, with warmth, the childhood of his youngest son, Feng Xinmei, who was nicknamed Engou. The album is now with Feng Xinmei's son, Feng Yu.

|

|

[Photo provided to China Daily] |