RESOURCES

2018-04-23 Source:China Daily

Boshan Mountain incense burner, popular during the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220), provided by Hebei Provincial Museum.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Over the centuries China has shown itself ready to adopt new concepts, cultures and products and eventually make them all its own

"Such was the continuity and wholeness of Chinese civilization that anything brought to it and considered foreign would ultimately be internalized once it was adopted," says Zhao Liya, a book editor turned historian who has just written for the catalog of an exhibition at the Cernuschi Museum in Paris titled the Perfumes of China - the Incense Culture of the Imperial Times. The exhibition is a joint effort of the French museum and the Shanghai Museum.

"When foreign spices entered China in huge quantities during the Tang Dynasty (618-907) between the early seventh and the early 10th centuries, it smelled exoticism, and it was in this that their attraction mainly resided."

Bronze lion-on-lotus incense burner dated to about one millennium ago.[Photo provided to China Daily]

These spices included, most famously, musk, a strong-smelling reddish-brown substance secreted by the male musk deer. Another was ambergris, a solid, waxy, flammable substance that was dull gray or blackish, produced in the digestive system of sperm whale.

The former came largely from the Eurasian steppe, where the deer roamed, and the latter is believed to have been swept ashore by waves of the Arabian Sea. Both eventually arrived in Tang Dynasty China through the Silk Road, a winding route that threaded its way across Eurasia, connecting ancient China with cities as far-flung as Rome and Alexandria.

However, Zhao says, a little more than half a century after the demise of Tang, the Song Empire (960-1279), founded after a brief period of chaos and fragmentation, imbued the spice culture with new significance, a meaning rooted in the past and considered today as quintessentially Chinese.

Bronze Boshan Mountain incense burner unearthed in South Korea, attesting to ancient China's exportation of its scent culture.[Photo provided to China Daily]

"During the time of Song, incense-burning became an integral part of the life of the literati, whose traditions and values were celebrated by the whole of society, from the emperors down," Zhao says. "Consequently, the whiff of luxury previously associated with using expensive spice gradually faded, replaced by a more casual, relaxed attitude.

"Inhaling scent was supposed to nurture introspection, a state of being that ideally should form the daily reality of a culturally minded and inform poetry writing. Thereafter, pursuing novelty and flaunting wealth was deemed irrelevant.

"This new ideal spawned a whole new aesthetic, with golden or gilt silver incense burners featuring intricate decorative patterns giving way to pared-down designs, often realized in mutely colored (pale greenish blue, for example) porcelain."

Fresco from the Five Dynasties period (907-960) showing a Buddhist monk holding an incense burner with a long handle.[Photo provided to China Daily]

This process of localization is inevitable, enabled by a tradition that had extended far back beyond the point of foreign spices' entry, Zhao says.

"Chinese used spice/incense long before the terrestrial Silk Road was opened." (In history, the terrestrial Silk Road was complemented and enhanced by what is known today as the maritime Silk Road, first formed around the first century BC but which only flourished when the waning fortunes of Tang led to intermittent interruption of the terrestrial route, around the ninth century.)

"In Chinese antiquity, that puff of smoke was believed to be able to facilitate communication between man and heaven," Zhao says.

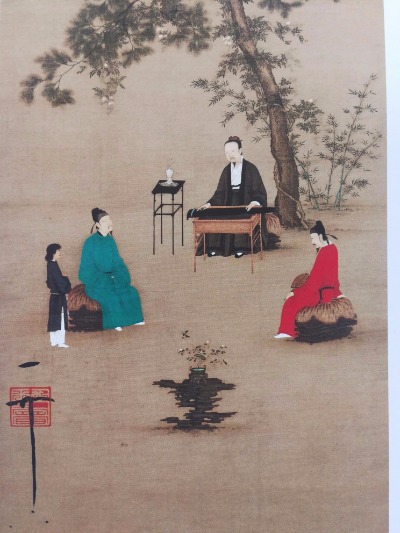

A porcelain incense burner as it appeared in a painting by Song Emperor Huizong, who himself is depicted as the man in black.[Photo provided to China Daily]

"Later it was expected to infiltrate and purify the mind. In between, the Tang Dynasty represented a distinct chapter, full of color and spice, literally and metaphorically. But it was in no way the entire story, or its most enduring part."

Jiang Jie, director of the Famen Temple Museum, about 110 kilometers from present-day Xi'an, Shaanxi province, believes that as far as spice culture is concerned, internalization was a perennial process, even during the Tang era. From the temple's underground crypt, many Tang-dynasty incense burners and related wares have been unearthed, testifying to a populous culture that was a veritable phenomenon.

"Very often during the Tang era, spice for burning came in the form of little balls that mixed spice powder with honey," Jiang says. "This was very much informed by the making of traditional Chinese medicine, whereby different ingredients were ground and then kneaded into round pills, with honey serving both as bonding agent and sweetener."

A porcelain incense burner as it appeared in a painting by Song Emperor Huizong, who himself is depicted as the man in black.[Photo provided to China Daily]

"But of course, with spice pills there would not be too much honey, for fear that it became incombustible. And not unlike Chinese traditional pills, the spice ones were also coated in wax for storage."

In addition, the Tang people experimented and came up with their own recipes for mixing different spices, to complement the existing ones brought to China along the Silk Road.

In 1975 the discovery of a sunken ship by South Korean fishermen southwest of the Korean Peninsula yielded vast amounts of porcelain - more than 20,000 pieces in total. Many were incense burners.

Bronze quadripod from Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC).[Photo provided to China Daily]

"The ship and its load have been dated back to China's Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), an era that directly followed the Song," Jiang says. "It is clear that by that time China was already exporting its own spice culture and paraphernalia to other countries."

In fact, if you listen to Zhang Deshui, director of the Henan Provincial Museum in Central China, two-way or even multi-way exchanges are what lie at the origin and heart of the formation of all civilizations.

"People talk about Zhang Qian (164-114 BC), the Han Dynasty explorer and Silk Road opener who traveled from the Chinese heartland to West Asia and then back," Zhang says. "But close study has revealed that the exchanges, cultural and material between China and the vast Eurasian landmass lying to its west and northwest far precedes Zhang Qian's historic journey. In a sense, the ancient Silk Road existed long before its 'official' opening."

Incense cage placed on top of an incense burner, from the Warring States period (475-221 BC).[Photo provided to China Daily]

One example involves renowned bronze wares from China's Shang and Zhou dynasties (c. 16th century-221 BC). Coveted by museums and private collectors worldwide, these wares, with their bewilderingly intricate and wildly imaginative designs, represented a height in the development of ancient Chinese art.

"However, bronze smelting techniques first appeared in western Asia about 7,000 years ago, more than two millennia before its eastward move brought it to China, where it was influenced by Chinese pottery making," Zhang says.

"Such influence, combined with the invention of mold casting by the Chinese, led to profound changes. Bronze knives and swords beloved by the steppe people were replaced by containers of food and wine, some of giant size. Apart from serving as cooking utensils, many of them also performed a ritualistic function, one embedded in the spiritual realm of our ancestors. And that is how they entered the Chinese cultural vocabulary once and for all."

Jiang Jie, director of the Famen Temple Museum.[Photo provided to China Daily]

Two millennia on, Emperor Qianlong (1711-99) of Qing, China's last feudal dynasty, turned to ancient bronze wares in his effort to revive an aesthetic he considered classically Chinese. The emperor, a diehard jade lover, commissioned numerous pieces of green jade carvings, all meticulously rendered as patinaed bronze wares. (Jade was once an important commodity on the Silk Road, so famous that some scholars have suggested renaming the Silk Road the Jade Road.)

Other things that gradually spread from the west to ancient China included the cultivation of wheat and the raising of goats and horses. All that happened roughly along the Silk Road, but before its inauguration.

Rong Xinjiang, of the History Department of Peking University, whose research into the ancient Silk Road started in the mid-1990s, believes that there were also many cases of parallel development, along a route that enabled and expedited exchanges.

"Where funerary traditions are concerned, gold face covers have been discovered in a Tang Dynasty tomb site in Ningxia Hui autonomous region, northwestern China. The decorative sun and moon-shaped gold plate on the forehead of the tomb-owner indicates that he was an adherent of Zoroastrianism, a religion that originated in ancient Persia and was widely adopted by the Sogdian people, the dominating traders on the Silk Road. On the other hand, covering the face of the dead with pieces of jade was a common practice for the rich and powerful in China between the 12th century BC and the third century AD.

"Are there any connections between the two? More concrete proof is needed before we draw any conclusions. Sometimes I am more tempted to believe that by destiny or happenstance, members of different civilizations may have arrived at the same destination, via different routes. While we dust away the desert sand to reveal the spider's web that was the ancient Silk Road, it is equally important not to make forced links."

But it is always satisfying to be able to pick up two loose threads and reconnect them, says Jiang Jie of the Famen Temple Museum.

"While the spice culture took hold of people's imagination in China, with the import of Chinese paper, ancient Persian rulers were finally able to end the practice of perfuming their strong-smelling parchment, before sending their written edicts to different corners of the vast empire.

"It is commonly agreed that people who have taken up a meaty diet generally have stronger body odor than those who have not, and are consequently more reliant on scents. That explains why in ancient times many kinds of spices came from the northern steppe.

"It also explains why the use of spices mainly took on two different directions in the ensuing era: for Western people, they turned into liquid perfume, applied directly on the skin; for Chinese, they became incense for burning, whose aroma permeates the surroundings."

One typical form of incense burner from the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) is the bo shan lu, or "Boshan Mountain burner". True to its name, the upper half of the burner rises from the cuplike base in a swirl of gold and silver, punctuated by pores from which plumes of smoke would emerge and rise.

"Most people believe that the burner evokes the sea-surrounding fairy mountain in ancient Chinese literature, a mountain upon which deities would descend during their earthly visits," Jiang says. "But others have suggested that the shape of the burner actually came from West Asia, with the mountain probably referring to those ones described in Buddhist scriptures.

"An indigenous creation or a Silk Road import? Debate is likely to rage forever. Either way, shrouded in the mist emanating from an ageless work of art is the landscape for mind's travel."