RESOURCES

2015-05-09 Source:China Daily

Handwritten letters in different languages.

A sunny morning breaks in Shiquan, a mountainous county in Northwest China's Shaanxi province, as Zhao Mingcui begins to strap postal items onto the sides and the back of a motorbike ahead of her journey. Every second or third day in a week, she delivers mail to the villages nearby, a job she has held for almost two decades.

It's around 9 am. But Zhao, who often uses dirt bikes and boats to reach remote areas, is still fussing over a handwritten letter inside a sealed envelope. Either the intended recipient's address isn't clearly marked, or she wants to ensure that the person is available at a given time to receive it.

After making a few phone calls to track down the addressee, she starts her lightweight Honda.

Zhao, the 42-year-old China Post mail carrier, is concerned with the fate of the single handwritten letter in her post of mostly newspapers and small parcels of the day.

Even until 2002, she would take dozens of letters and telegrams to the villages, but now paper communication is down to an average of two or three a week-mainly from soldiers to their families or others in need of village council attestations of documents such as marriage or birth certificates, she says.

China Post mail carrier Zhao Mincui (right) brings letters to villages in Shaanxi province. She deliversnewspapers and small parcels, among other items.

In China, where some 700 million people from a total population of nearly 1.4 billion are estimated users of the Internet, Shiquan isn't the only place to signal the fast disappearance of handwritten letters.

According to the State Post Bureau, a central government organization that oversees China Post-the sector's monolith-the country handled 5.6 billion "paper post" in 2014, showing a 10 percent drop from the previous year. Letter-post articles included newspapers, magazines, commercial correspondence, money orders and typed or handwritten personal letters, with the latter in the least volume.

In addition, interviews with dozens of postal officials, countryside dwellers, analysts and scholars suggest that the era of handwritten letters is likely on its last legs in China.

A top official of the bureau in Beijing, however, denied the possibility of a wipeout, saying that for many people such as prison inmates, writing and receiving letters still work as basic rights where access to phones and the Internet is legally barred. Today, there are 53,000 post offices on the mainland. In the 1980s, there were 70,000 or so.

While it is true that hundreds of new post offices have been opened in villages and small towns in China since 2010, in the years before, post offices had been shut down also as part of a reforms program to prepare China Post for the modern world. It has since successfully diversified into express mail, small-package deliveries (of up to 2 kilograms) and big logistics, among other newer ventures.

Handwritten letter in a foreign language.

The reforms also led to the segregation of telecom from postal services that were previously bundled together.

In the past decade or so, as technology started to spread across Shiquan, rich villagers took to cellphones and eventually gave up writing letters. Only those that didn't own phones stayed in touch with loved one through the conventional delivery of messages, taking days.

"But now almost every family in a village here has at least one cellphone. So, letter-writing has reduced a lot," Zhao says.

In 2013, some 88.7 percent of every 100 Chinese on the mainland subscribed to mobile or cellular telephony, according to International Telecommunication Union, a Geneva-based United Nations agency. There were only 2,000 Internet-using families in China in 1993, a research paper of government think-tank Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said.

The trend of falling paper communication is global.

The worldwide letter-post traffic was 350.9 billion items in 2012, when a 3.5 percent slide from the earlier year was recorded by Universal Postal Union, another UN body.

In China's case, the e-commerce boom-more noticeable than in some other parts of the world-has forced traditional businesses to change.

Handwritten letters.

On the mail trail

Shiquan is located to the south of provincial capital Xi'an and is home to 180,000 people and 202 villages where crop farming, silk trade and tourism drive the local economy. The Han River runs through many of the villages, which are surrounded by the Qin Mountains and can be accessed by road and rail.

Zhao, the mail carrier, has been in media spotlight for winning government awards for her work in rural China. She and 14 other colleagues look after the distribution of mail in the county. China Post has a total of 105,000 delivery people, a good number working in the company's logistical support business.

Her first stop is at a site near the river, where a new railway line is being constructed. It is Da Gou village, where she delivers a few copies of the Shaanxi Daily, printed two days ago, for the men at work. A train passes though a tunnel overhead and yellow mustard flowers sway in the breeze as she then ascends a dusty road on her bike.

Newspapers are a big component of Zhao's weekly routine.

She can earn on top of her basic monthly salary of up to 2,800 yuan (around $450) by taking more and more of the subscribed papers to the villagers.

Next, on her way to the Shi Li Gou village, Zhao hands over a small parcel to a young man. He is thrilled to receive the box containing something that he had ordered online. Like many others in the countryside, he prefers to buy goods at virtual marketplaces, and can receive them by post.

Then, at the house of a village secretary of the Communist Party of China, Zhao delivers some newspapers for people to read during meetings.

Some among the village's older generations, like He Cui, 52, and Shi Ling, 61, describe handwritten letters as old-fashioned. The first woman says that she liked to receive letters years ago, when her children wrote to her from the cities they lived in, but she hasn't write one herself in this century. "The phone's there to talk," He says.

"Women in the village don't have the time to write letters," Shi says of their work at home and on the farms.

Handwritten pictograph.

Zhao had joined China Post as a mail carrier in 1991, at the behest of her parents, who run a grocery store in Gao Kan village where she lives with her husband and their two children when she isn't staying at the company accommodation in the county. Zhao went to middle school, but not beyond.

Her initial years on the job were harrowing, faced with the challenges of rough weather and the area's underdevelopment back then, but gradually she grew fond of it.

"For me, salary isn't the point, joy is. I bring cash remittances to retirees in the village," Zhao says of the aspect of her role that she most enjoys.

As she rides along the narrow roads of the rocky countryside, several people greet her. She is the star "post woman", who crosses meandering streams and scales rain-washed slopes to reach corners of the county, where a few villages are possibly inhabited by just a handful of families.

As afternoon approaches, Zhao makes a quick trip back to Da Gou where at the village clinic she gives Zheng Shibo, a 38-year-old doctor, a bunch of comic books that arrived in the mail. Zhao's post also contains books for the villagers every month.

"He sometimes watches cartoons online but I'd like him to read some real books," Zheng says of her 12-year-old son for whom she ordered the comics.

It has been more than a decade since Zheng has stopped using pen and paper to write letters. "It was a great feeling to receive letters. People's emotions came out very differently," she says with nostalgia. "Emails and phone calls are very direct. They've killed the charm of communication."

As afternoon fades into evening, Zhao rides on a boat along the Han River to visit a few other villages.

"It's unrealistic to think that handwritten letters will continue to survive," says Zhao Minbin (not identified as someone with any relation to Zhao Mingcui). The 46-year-old guard at a primary school in one of the villages in Shiquan, isn't mourning the loss of letters. He is a fan of modern technology. It has made his life smoother.

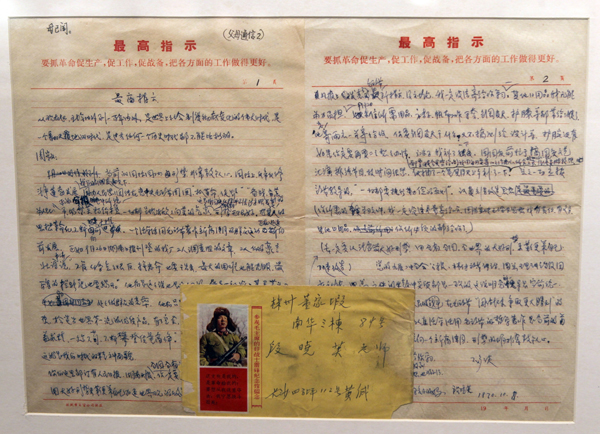

A collage of personal letters from the 'cultural revolution' (1966-76) days at a Renmin University of Chinaexhibition in Beijing.

Museum of letters

The most significant drop in paper communication was noticed in China in the past two years.

The amount of business correspondence and advertisement letters being mailed through traditional post in China have been lower, historically, as compared with developed countries in the West, explains Bian Zuodong, director, Division of Universal Service Garantie, an arm of the State Post Bureau.

That's why the Internet and mobile phones have become popular tools of communication in China, he says, citing it as a key reason for the reduction in letters.

The cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and the eastern province of Zhejiang, handle the maximum amount of paper communication. These are also places where China Post can hope to keep its business growing because despite the influence of technology across societies in urban China, the population density creates demand.

In addition, China Post is partnering the country's e-commerce industry with its small-package delivery system, Bian says, adding that China Post is also looking to increase its presence further in the countryside. Until February, 8,051 new post offices have been built, of which, 6,710 are already functioning.

"Although letters' delivery won't die out, ... the business model of postal companies would change from traditional services to modern logistical services," Bian said during an interview in his office in Beijing, last month.

The Internet started to gain popularity in China between 1995 and 2000, with the early birds being white-collars in the big cities and elite college students. But even until a few years later, the then emerging world of cyber communication had little influence on the writing of letters.

The Internet started to gain popularity in China between 1995 and 2000, with the early birds being white-collars in the big cities and elite college students. But even until a few years later, the then emerging world of cyber communication had little influence on the writing of letters.

In April, Zheng Shibo, a doctor in Da Gou village, Shiquan county, receives comic books for her son by post.

Most young Chinese read printed books and handwrote personal letters in the mid-2000s.

But by 2010, even older Chinese-born in the 1950s or 60s-were making efforts to blend in with new technology, while traditional reading and writing were getting marginalized in the public sphere, according to Chang Jiang, assistant professor, School of Journalism and Communication, Renmin University of China.

"Email and instant messaging software gradually replaced the fundamental role of writing and via-a`-vis communication," Chang, who is in his 30s, wrote in an e-mail to the paper, identifying 2000-2005 as milestone years that changed the face of communication in China.

While today, more Chinese in big cities seem to be hailing taxis from the comfort of their living rooms than those waiting out on the streets, thanks to smartphone applications, and children learn Chinese characters on touch-screen devices, there's also a realization in some quarters that the letter-writing tradition must be protected before it vanishes.

The Renmin University of China, for instance, has a museum for Chinese family letters in Beijing, where stone carvings and handwritten letters, dating back to the late Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), are showcased alongside contemporary samples, giving glimpses of the evolution of post in China since the days of horse-backed mail carriers.

A recent study by the university's Family Letters Cultural Studies Center, which manages the museum, found that only seven percent of some 1,130 individuals surveyed, was still sending or receiving handwritten letters, according to Zhang Ding, the executive director for the center.

In 2000, Yang Jianxin migrated to Beijing from eastern China's Shandong province. He bought a cellphone and stopped writing letters that year.

The 42-year-old taxi driver says: "I miss the ritual of waiting for letters to arrive."